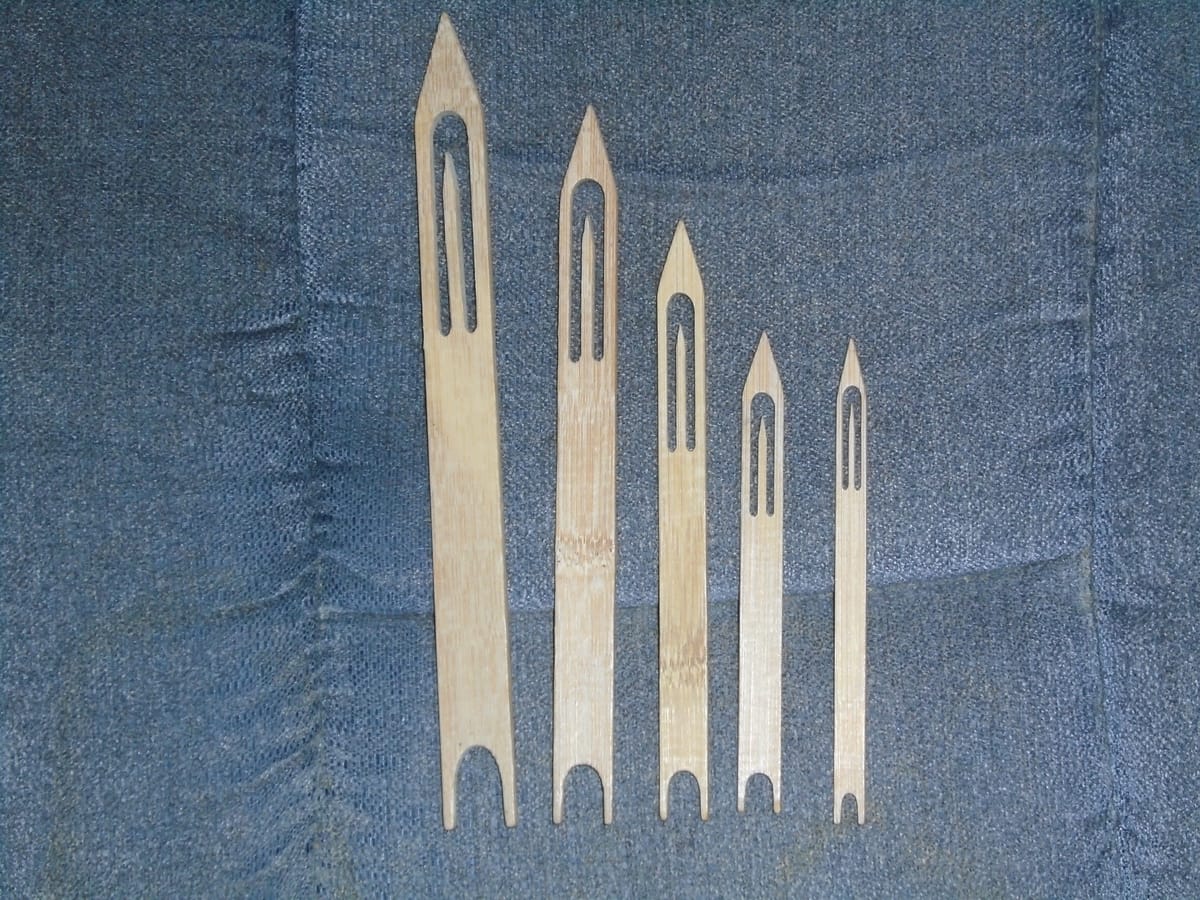

Tools of the trade

You've seen my regular netting needles, and these are not they. My regular netting needles are made of steel, they're very narrow, and they carry a lot of string (or thread, depending on the size). These? They're bamboo, they came from eBay, and their sole purpose is SCA demonstrations. At least they do look as if they might be something like birch or ash, so I don't need to stain them, which I did think I might. But they're not massively effective - even the very small one is too wide to make a decent small-gauge mesh, and they don't carry that much string because you wind it round that point in the middle. I honestly can't see the purpose of doing that; they'd be much easier to wind if they were the same at both ends, meaning if they had that indentation you see at the base at both ends. Nonetheless, this is the time-honoured traditional design for a netting needle, and frankly I think it's pants. The single thing it has going for it is that you can use the larger needles as mesh sticks for the smaller ones.

For the kitchen, I've rather gone the other way. I have bought a small, very modern, reassuringly cheap, electric spice grinder; because nobody is going to see me doing mediaeval (or any other form of) cooking, so I am bothered if I'm going to wear myself out using a pestle and mortar. I have also ordered a paperback copy of Forme of Cury, which is the earliest known English cookery book, dating back to about 1380 (in other words, it's contemporaneous with many of the recipes in the book accompanying the Orlando Consort album I posted about on Wednesday). I will admit to having been very confused when I first saw those words. I kept seeing Forme of Cury next to mediaeval recipes online, and thinking to myself "I don't see how that's a form of curry!". Nope. Nothing to do with curry; it is the title of a recipe book, and "cury" is basically the same word as the French cuisinerie, meaning cooking.

This paperback is going to be useful, although I've been warned it may not be great quality (it appears there are quite a lot of versions consisting merely of assembled scans of the original MS, although this one does say that the recipes have been "translated", whatever exactly that means in this case). It is, at the very least, something I can easily take into the kitchen, which I can't with my laptop. I was pointed to a PDF version on the Internet Archive, so I downloaded that and have been having a look through it; though I've had to sew my tunic at the same time, since the pages load so slowly (there are over 200 of them, including the 18th-century introduction). If the print copy turns out to be bad, I can always annotate it from the PDF.

But... by the time I was about halfway through the PDF, I was starting to feel as if my head was about to explode. The Orlando Consort's recipes had not in any way prepared me for this. You think you're looking at a sweet recipe, and then suddenly it calls for meat. You think you're looking at a savoury recipe, and then you get sugar and/or honey. It's as if they had absolutely no concept of main courses and puddings, and they just jowled the whole lot up together. (I don't know whether the Orlando Consort carefully selected their recipes to avoid this sort of thing, or whether it's just that most of them aren't English, and perhaps this weird sweet/savoury amalgamation was purely an English thing. But whatever it was, I think it's gross; I absolutely cannot stand sweet in my savouries. At least, anything sweeter than parsnips, and those are not really that sweet.) The point where I finally gave up in disgust was when I got to the recipe for "Payn Ragon", which, as far as I can tell, is a kind of ginger version of Kendal mint cake; it's mostly sugar and honey. Ah, I thought, finally an all-out sweet recipe; though to make it vegan I'll have to substitute date syrup or something similar for the honey. And then, right at the end of the recipe, it told you to serve it with fried meats and I thought... I'm out. They were clearly all insane.

Now, to be fair, this recipe book did originate from the court of Richard II, so most of it is not everyday fare (though one or two of the recipes clearly are, especially at the beginning where there are a couple of recipes using beans). You can tell, because there's a great deal of saffron used, as well as sugar and honey. Saffron, then as now, was extremely expensive... though it does seem to have been used quite often as a colourant rather than a spice, which would not have required so much of it. And sugar, also, was a status symbol at the time, so it appears that King Richard's cooks got over-excited and put it in almost everything, along with the saffron. But still, King Richard must have enjoyed it; you don't hear of him sending for any of the cooks and complaining that his venison tastes sweet. The 18th-century introduction, without specifically mentioning all the sugar, does say that many of the "messes" (meaning dishes, though I suspect it may still be a startlingly appropriate word with its modern meaning) seem very strange to the modern palate, but de gustibus non est disputandum. It adds that the Romans strongly disliked pepper and lemon juice, using them both only as scents. (It doesn't mention that the Romans were also exceedingly fond of a sauce made from rotten fish. I'm reminded of the interpretation of "SPQR" given in an Italian translation of one of the Asterix books I once saw, which was "Sono pazzi, questi Romani" - in other words, "These Romans, they're crazy!") And there is a surprisingly modern echo to the 18th-century editor's views on the number of ingredients involved, suggesting that to use so many different herbs in one dish might be injurious to health! I couldn't help thinking of the (very) modern idea that it's somehow good to have as few ingredients as possible... though I still haven't worked out exactly how that squares with the advice to eat as many different plants in a week as you can (one is supposed to aim for 30, but I tried counting once out of curiosity and got to about twice that figure without specifically trying, so I shan't bother doing that again).

Anyway. This recipe book is going to need some adaptation, and not just coming up with vegan versions of the recipes that aren't already vegan. I need to take each recipe, decide if it really wants to be sweet or savoury, and tweak accordingly, because I am not eating any of these bizarre 14th-century chimaerae as they stand, thank you very much. The SCA is a barrel of fun, but there are limits!