Middle-Aged spreads

Ah, mediaeval recipes. They're eternally fascinating (I saw one recently which began "Take a sausage and kerf hym in gobettes" - what's not to like there?), but I can't help feeling that they were more mnemonics than actual recipes. The actual recipes, clearly, were in people's heads. The reason I say this is that you were very rarely given any quantities. I mean, look at this one: it's called "Perry of Pesoun", where "pesoun" are peas. Not the green kind popular today, though. If you want a mediaeval flavour, you need to use split peas, which are about the closest modern alternative.

Take pesoun and seth hem fast, and couere hem, til thei berst; thenne take hem vp and cole hem thurgh a cloth. Take oynouns and mynce hem, and seeth hem in the same sewe, and oile therwith; cast therto sugar, salt and safroun, and seeth hem wel therafter, and serue hem forth.

So we're not told the proportions to use, which is entirely normal for the period, and in fact there's quite a lot else we're not told. I'm assuming that "cole" here just means "strain", and you're not being asked to push the split pea pulp through a cloth to turn it into a fine purée, because I'm not sure a cloth would take that... but, all right, you've strained your peas, so then you mince your onions and boil them in the same "sewe" (I don't recognise that word, but from context it clearly means the water you boiled your peas in) with added oil. Then you add your sugar (in my case I really don't - I like sweet things as much as the next person, but I hate sweet in my savouries), salt, and saffron, give the onions another good boil, and then "serve them forth"... but, hang on, what exactly are you supposed to do with the peas? It doesn't say. It doesn't even say how much water you need to use, but I'm thinking as little as you can get away with, at least unless you're trying to make a soup. And I'm not at all sure what a "perry" is in this context, so for all I know it may well be a soup.

Now, you know me. I'm up for all kinds of strange culinary adventures; and the fun thing here is that a surprising number of mediaeval recipes were vegan. I thought there'd be hardly any, but no, there are lots of them about, because for most of the Middle Ages you fasted during Lent, and "fasting" meant you avoided meat or dairy (though, oddly, you could eat fish). They even had almond milk, and used it freely:

Take a porcyoun of Rys, & pyke hem clene, & sethe hem welle, & late hem kele; þen take gode Mylke of Almaundys & do þer-to, & seþe & stere wyl; & do þer-to Sugre an hony, & serue forth

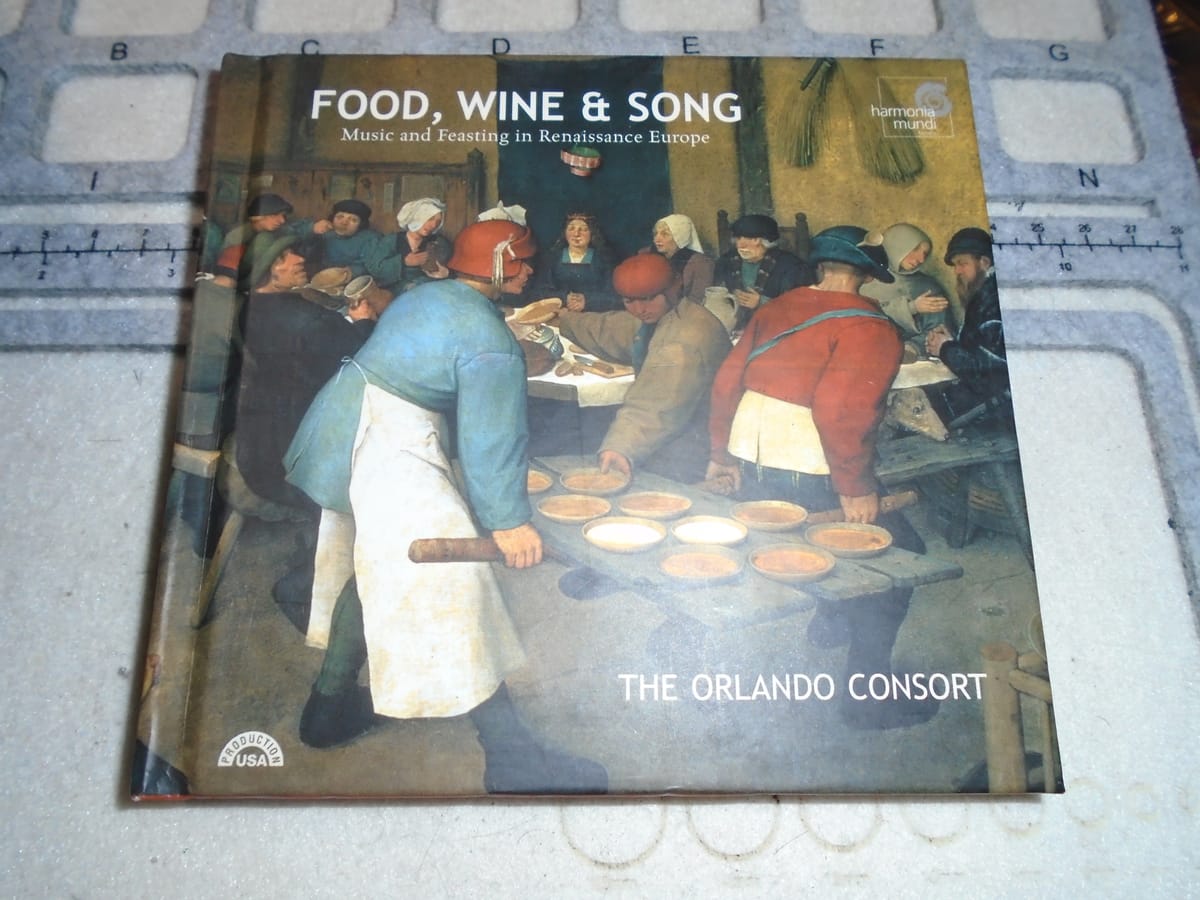

Nonetheless, I'm not sure I'm ready to pitch straight into mediaeval recipes without some kind of expert guidance... and this is where the Orlando Consort come in. This was a small a-capella singing group specialising in early music, some of it very early indeed; and, in particular, they made the album shown in the feature photo. I managed to pick up this one very cheaply from eBay; it is out of production. (I used to have one before 2016, but...) And, while the music is truly wonderful, I can't actually listen to the CD, so I'm also going to have to get a download; however, the download does not have an electronic version of the glorious little hardbacked book that goes with it.

This book is amazing. It runs to over 100 pages. There are, as you'd expect, notes about the songs themselves and their historical and geographical contexts (they come from several countries and were written over a period of about 350 years). There are the words, with translations where needed and occasional scholarly footnotes saying things like "this probably had an obscene double meaning". (Quite a lot of mediaeval songs did, and in many cases it wasn't so very double, either.) And then... there are the recipes.

I misremembered; I thought the original versions of the recipes were presented alongside their modernised versions, but they aren't. I'll have to go looking for them online. But they got a number of well-known chefs in, including Clarissa Dickson Wright, to produce modern versions of a selection of 14th- and 15th-century recipes, nineteen of them in all; one of them (Leeks and Beetroot in Raisin Sauce) was very popular in mediaeval times but probably dates originally from the Roman era. There are both savoury and sweet recipes, the latter including the oddly specific Orange Omelette for Pimps and Harlots; sweet omelettes were popular at the time, though one never hears of them today. (I did try this one shortly after I bought the original copy of the CD, as I was just vegetarian rather than vegan at the time. I can therefore tell you that, first of all, it does also work for respectable people, and secondly it's not actually very sweet; I had to add more sugar. Tastes, however, will vary.) There is a version of "green sauce", made primarily with parsley and basil, which was so popular that you could buy it in the market ready-made; and, last but by no means least, Baked Apples for a Drinking Session. The original recipe was baked on, of all things, a drop spindle, so it has had to be adapted even more than some of the others. You can choose to make the modern version as either dumplings or fritters, and in either case I suspect it's pretty messy to eat.

From what I've seen so far, this recipe selection is quite a representative one, although it does lack any recipes for poudre douce and poudre fort, two very widely-used spice blends of the era (the latter being a kind of mediaeval curry powder, using pepper rather than chillies - as, indeed, they did in India itself for a long time, until chillies eventually made their way over there and were enthusiastically adopted). I'm pleasantly surprised at just how varied and imaginative it was; most people, unless they were really very poor, seem to have had a pretty good diet. I hadn't really latched on to this fact earlier, because I was used to thinking in terms of late mediaeval/early modern cuisine, which tended to be very heavy on the meat to the point where you quite often wouldn't get served any vegetables at all (you'd have bread with it, or, once they were introduced into this country, potatoes). No doubt this came about because the Lenten fasting rules were gradually relaxed. (It's worth noting that they are still very strict in the Greek, and probably therefore also the Russian, Orthodox Church. I have Greek Orthodox friends who observe a lot of fast days, and on those days they are strictly vegan - no faffing about with fish.)

So I shall probably be having a little bit of quiet culinary fun in the near future; all I have to do now is work out the best way to seeth my pesoun in the microwave, and I'm good to go!