Lost in translation

Does poetry translation count as a craft? Well, I'm going to count it.

At some point in the late 00s, I discovered this book and it completely blew my mind. I was already familiar with some of Hofstadter's other work, so I was expecting it to be good; it was a great deal more than that. It was amazing. Hofstadter takes a sweet, simple little sixteenth-century poem with three-syllable lines, uses that as his recurring theme, and then he (along with various other people) translates it in a bewildering variety of different ways. One or two of them I don't really count as translations, since the concept has been stretched too far; but only one or two. If I recall correctly there are about 80 of them. And, between translations of this poem, he goes off on all kinds of fascinating literary, creative, and cognitive-science-related tangents.

So I thought, "well, that poem's been done to death now; I could not possibly produce my own original translation". And then I did. And then I did it again, twice, this time specifically addressed to Porthos and d'Artagnan in fairly quick succession due to a couple of minor illnesses. (Athos, at the time, was in rude health; sadly he's not now, but I don't think I could bear to do a translation for him, because he's not going to get better.) I was especially pleased with d'Artagnan's version; you see, one of his nicknames is "nightingale" (not merely because he has a beautiful singing voice - he's also a creature of nocturnal habits!), so I had to use that because it scanned so well. The first two lines, therefore, were:

Nightingale,/songbird, hail...

which set me up perfectly to end the poem with

God make our/songbird hale,/nightingale.

So I had a little symmetry there that even Marot didn't have. And by this time, the poetry translation bug had its teeth firmly into me and I was well and truly hooked.

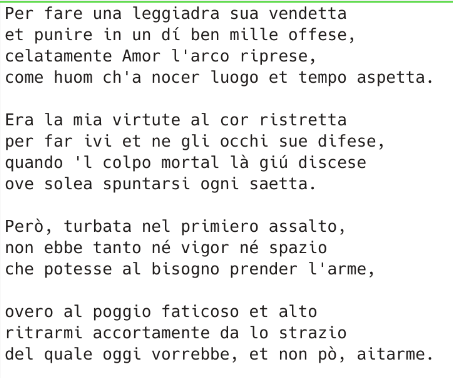

I went and taught myself Italian, for no other purpose than to translate Dante and Petrarch (not that it didn't come in useful elsewhere, but that was the driving motivation behind it). And, after some months of application and an incredible amount of extensive reading (I subscribed to an Italian magazine, which did contain some gems, but a surprising amount of it was in-depth articles about our royalty!), I was ready to tackle something like this.

If you are using a screen reader I am really sorry. Unfortunately there is no way of laying out verse without a lot of extra blank lines, so I have to use an image. You can find the text here if you wish.

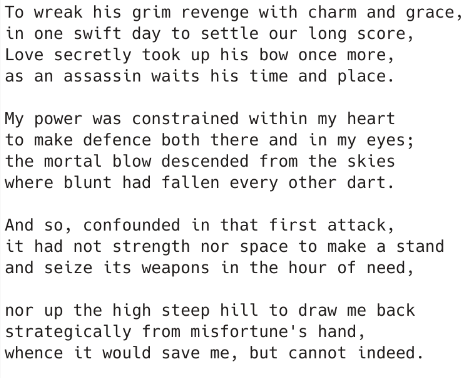

Anyway, this is what I did with it:

If you're not an Italian speaker, there is one crucial thing to note, and that is the fact that Italian poetry elides. If you have two vowel sounds together (like fare una in the first line), they are pronounced as one vowel; so Petrarch was not, in fact, terrible at scansion. Also, slightly less importantly, the average Italian word has more rhymes (often a lot more rhymes) than the average English word. Hence Petrarch could easily turn out a whole slew of sonnets that rhymed like this one: ABBA ABBA CDE CDE. In English this is a lot harder, though it can certainly be done. Usually, though, it is one constraint too many for a translation of this sort, which is why my version rhymes ABBA CDDC EFG EFG. (I am tangentially reminded of a friend at university who, when challenged to find a rhyme for "aardvark", proceeded to write a sonnet in which every single line rhymed - sort of! - with the given word. But you did have to count things like "car park" as rhymes.)

I always tell people that poetry translation is a bit like sudoku with words, because all the parts have to fit together. You have to stick as closely as you can to both the meaning and the form. You may need to paraphrase a little; for example, I've translated punire... ben mille offese (literally "to punish... a good thousand offences") as "to settle our long score", which comes to exactly the same thing but isn't literally what the Italian says. To be honest, though, the rest of it is pretty much literal; and what enables a translator to do that is that there are many words and phrases that mean similar things, plus there is some fluidity with word order. So you are choosing a pair of words that rhyme from quite a large selection, and then nothing else in your two lines has to rhyme, so all you now have to do is adjust it to scan.

There is another thing about translation of older texts - not just poetry - that continually fascinates me. It's even there in that Marot poem. The poet is concerned that, if the sick maiden he is addressing does not get better soon, "tu... perdras l'embonpoint" (not even just "you will lose weight", but in the context "you will lose that pleasing plumpness"). In our modern age which appears to be obsessed with thinness, this reads a bit oddly to a lot of people. Now I personally have views about this one, and they are not very modern, so I am quite happy to translate as some version of "you will lose weight" with the implication that that is a bad thing. (Even then, I had a little difficulty here with Porthos' version, since at the time he was carrying far too much embonpoint by anyone's standards, including his own; he's since had bariatric surgery.) But in some of the older Italian poetry, most particularly in Dante, some of the imagery is downright weird and even gruesome to the modern reader (there's one sonnet in particular that goes on about someone eating someone else's heart, which is supposed to be incredibly romantic!), and the question is always... well, what do you do with that? And the answer is, you have a choice. You either go with it and bring all the weirdness across to the modern reader, so that it is as close as they can get to reading the original; or, and this is an equally valid approach, you translate so that, as far as possible, your translation has the same effect on your modern audience as Dante's poem did on his original audience. And I've done both at different times. The Petrarch sonnet shown here isn't especially strange to a modern audience, since even most people without an explicitly classical background are familiar with the concept of Cupid and get the idea that this is who we're talking about here; it's going to come across as old-fashioned and somewhat mannered, but for me that's part of its charm. So I suppose with this one I've taken the first approach; but I could just as easily have substituted for words such as "constrained" and "confounded", both of which are rather older words with a formal air about them, and replaced them with something breezier and more modern. (In this case I'd have had to substitute a full phrase, as I can't think of a direct replacement for either word that scans in the same way.)

A few years later I got to know an energetic American lady who was a stunningly good operatic soprano. She and her husband were based in London when I first met her, but to the great delight of both of them they were able to move to Manchester, where she wasted no time in setting up her own opera company. They put on a very good Anna Bolena, and then they decided to do Lucia di Lammermoor and I was originally asked to direct it (unfortunately I had to bow out a little later due to health problems), so I got a copy of the score. Which had an English translation. And the translation was so bad it took all I had not to hurl it at the wall in disgust. I thought... you know, if this is what passes for translation, I could easily make a good living out of translating operas.

I'd have really enjoyed doing that; but it never happened, because it turned out that if you want to get into opera translation, what you have to do is this. You don't just tout round a sample piece. You have to translate an entire opera, free of charge, which is several months' work, and then you send it to the English National Opera Company and allow them to use it. Then, if they like it enough, you hope they might commission you to do a paid one. And I thought... nope. I have not enough money and too much self-respect to go down that route.

Anyway, in the intervening years I'm afraid my Italian has gone a little rusty from disuse, so at the moment I am taking a year out from my maths degree to scrape the rust off; I've recently acquired the Don Camillo stories in the original, so the rust-scraping is a most enjoyable process. I have also replaced my copy of Dante's Vita Nova (the original was the most expensive book I've ever bought, while the replacement was a very reasonable price); however, I'm bemused to find that, though the poetry (which is what I'm really interested in) has been left in Italian, for some strange reason the rest of it has been translated into French.

Possibly I should be brushing that up as well!