And another thing...

Gina Barrett, owner of Gina B Silkworks, has a great deal to answer for. I'm on her mailing list, the reason being that her website is where I get my netting needles (and occasionally other things like weaving stuff, but I don't know of anywhere else in the UK who sells Pony netting needles). She, like me, is a multi-crafter, and she tends to sell mostly stuff related to the things she does; but the crafting love of her life appears to be buttons. I am always getting marketing e-mails from her trying to sell me button-making equipment and threads. And while I have to say she does make some exceedingly pretty buttons, I still don't quite trust a button made from thread to be functional. Buttons get a good deal of wear and tear, and I don't want to put beautiful hand-made thread buttons onto a garment only to have them go all frayed at the edges. So I look, and admire, and am not in the least tempted.

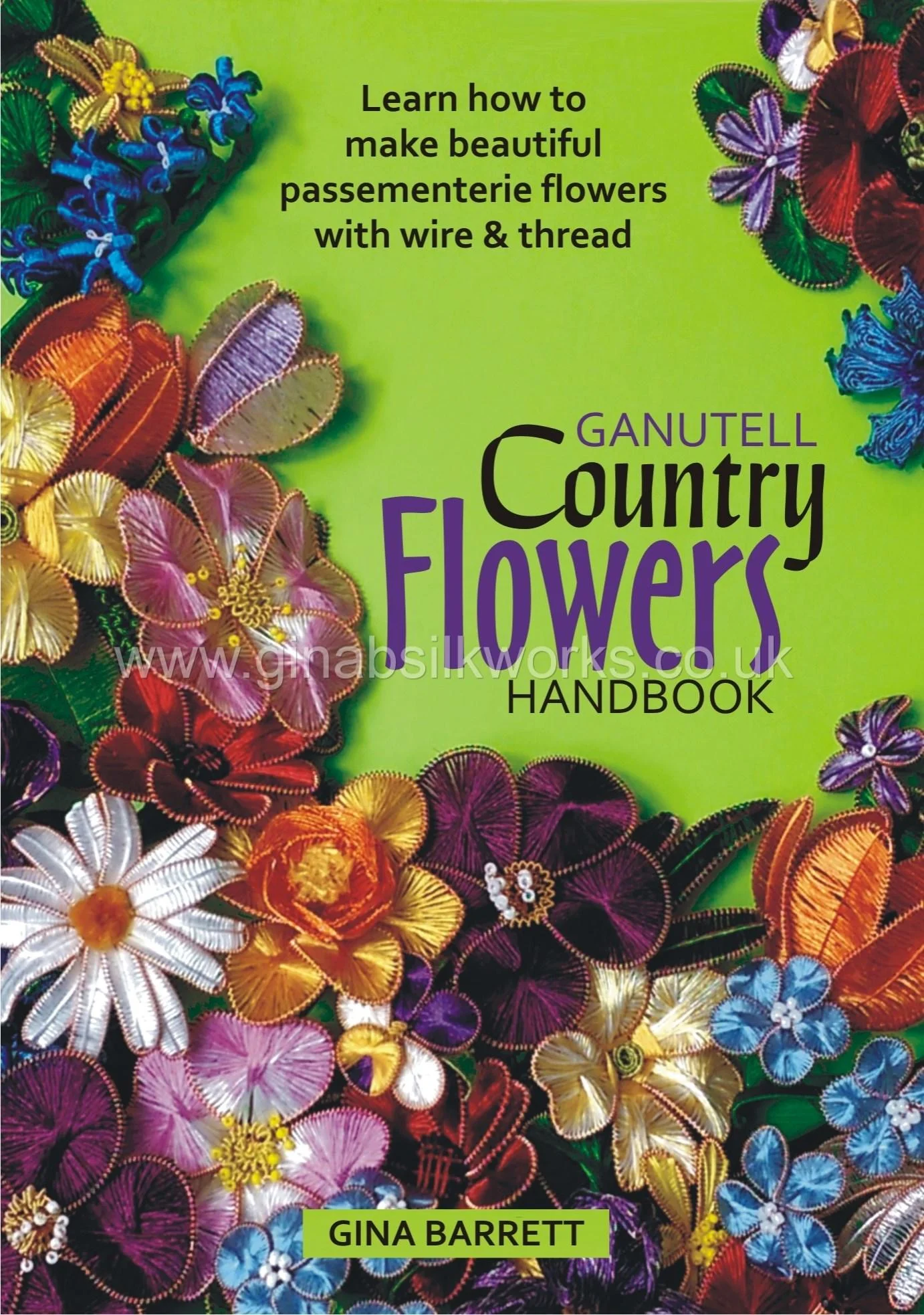

But then she sent me an e-mail about ganutell. I had no idea what ganutell even was; but the moment I saw what you could make with it, that was it. I was hooked. I have been looking around all my life for a technique that does, basically, this; there is plenty of information on how to embroider things like flowers, leaves, and butterflies, but actually making them out of thread is a whole different thing, and that was what I wanted to do.

Ganutell originated at some point during the Middle Ages, so it's also suitable as an Arts and Sciences activity within the SCA; the earliest record of it is in the 15th century, but it may be older than that. It is not known exactly where it originated, but it is known that it became very popular in Malta, and retained its popularity there right up to the present day (apart from a dip round about World War II); it's still possible to find ganutell decorations there, particularly in churches, and it is now considered a specifically Maltese craft. (If it's flat or very gently curved, you can make it in ganutell, so I should think there are a lot of ganutell crosses.) The name itself is a version of the Italian word cannottiglio, which appears to be a derivative of cannotto, a metal tube. This would (presumably) have been used to make the purl wire required for the craft; these days it is easy enough to buy pre-coiled purl, but it is expensive, so I shall be coiling my own as was done historically. Given that the original name is Italian rather than Maltese, it seems likely that the craft originated somewhere in mainland Europe and was imported into Malta, but not necessarily in Italy itself.

The flowers shown on the cover of the book seem to be the most typical kind of ganutell, but there are others. It is possible to do a version of the technique using thicker chenille thread, which gives a completely different effect. Ganutell pieces can also be embellished with beads; the forget-me-nots at the bottom right of the book cover are a good example, or larger beads can be used to make the body of a ganutell butterfly. The technique can be combined with embroidery to great effect to make certain parts of the design 3D, or it can be used on its own for either free-standing decorations or what Gina likes to refer to as "passementerie" (a term which seems to cover any kind of decoration applied to a garment while it is being made or after it is finished, rather than being part of the original fabric). I imagine it would be especially effective on hats, where there is not much likelihood that it will get crushed.

There is a form of stumpwork which is produced by wrapping small cardboard shapes tightly with thread and then sewing them to the fabric; it has a name, but I forget what it is. Because the resulting shapes look quite similar to ganutell, the two techniques combine particularly well. This is worth bearing in mind, but only for finished pieces which will never have to be washed!

I very much doubt I'll be doing anything like that, though. My main interest is in free-standing pieces, and the fact that it's also a) historical and b) highly portable is a huge bonus. Much as I love my netting, it can be a bit awkward to schlep about, especially if I'm making a large piece, as I am at the moment; but ganutell can go to an SCA event in a small bag, and will - as another bonus - enable me to hand out pretty little handmade butterflies to newer members. (Handing out small objects to new members is a fine tradition in the SCA. At the feast on Saturday night I found myself sitting next to Duchess Angharad, who is from Seattle and who has a metalworker friend who makes rather wonderful mediaeval-looking coins. Angharad has been handing these out to every new or fairly-new member she meets for, apparently, several years, and as a result of that I now have one of these little delights in my belt pouch.)

And if anyone needs a posy for a wedding, I'm now going to be able to make one that is genuinely pretty but won't either wilt before the speeches begin or drip all over their expensive suit. It'll still be mostly compostable (it's traditional to use silk thread, but cotton also gives excellent results, and that's what I'll be using), and the non-compostable parts will be fully recyclable. What's not to like here?

Oh... yes... there is, of course, the time element. I already have so many things I do in odd moments that I barely have any odd moments left; and right now I'm pretty busy with both the course work and the Puncetto Valsesiano translation (which is quite an undertaking, because of course it's not just translation - I also have to screencap all the images, rotate them back into true, clean them up, remove the Italian captions, and replace them with translations). I think I need to work out how not to be travel sick, then I can craft while I'm being given a lift somewhere.

Of course, I probably don't have to look at the rod while I'm coiling wire!